TDM exceptions (not just the three-step test) don’t allow all unlicensed AI development

TDM exceptions (not just the three-step test) don’t allow all unlicensed AI development

As autumn settles in and leaves begin to fall, one thing stays firmly in place: the judicial, policy, and academic focus on the intersection of AI development and copyright.

Much of the debate regarding AI training centres on the scope of copyright exceptions allowing, under certain conditions, text and data mining (TDM). As readers know, the EU copyright system provides for two such exceptions (Articles 3 and 4 of the DSM Directive). In the UK, a text and data analysis exception was introduced in 2014 by relying on Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, and a potential legal reform is currently being considered in that country. Beyond Europe, TDM exceptions exist in the copyright laws of, e.g., Japan (Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act) and Singapore (Section 244 of the Copyright Act 2021). In the USA, ongoing litigation around unlicensed AI training is testing the boundaries of the fair use doctrine.

As the global discourse shows, what is at stake is not whether AI training is copyright-relevant (there is no longer any doubt – if there ever was – that it is), but rather how to balance rightholders’ control, on the one hand, and the use of copyright works and other protected-subject matter by AI developers without permission, on the other. In other words: licensing versus exceptions.

TDM is not synonymous with AI

As discussed in greater detail elsewhere, it is important to clarify that no copyright exception – including those permitting TDM – covers the entirety of AI development. All existing TDM exceptions (including those referred to above) only encompass specified restricted acts. For example, both EU TDM exceptions cover acts of extraction and reproduction done for the purpose of TDM. Neither of them extends to the undertaking of subsequent restricted acts (see here).

AI training – by default – requires the making of copies, with the result that the right of reproduction is engaged several times. For the avoidance of doubt, in line with the wording of relevant legislation and case law, this exclusive right encompasses reproduction “in any form”. It is therefore irrelevant if the copies made are permanent or merely temporary. If a copy is made at some point in the process of developing an AI model, that copy is the result of a copyright-relevant act of reproduction. Hence, those that have argued that the process of development of AI models does not involve copyright-relevant reproductions – either because the copies are ‘intermediate’ copies, or that the AI models are merely being ‘inspired’ by existing works and subject-matter, or even referring to the idea/expression dichotomy and arguing that copying only involves ‘non-expressive’ parts of works – are incorrect, both from a technical perspective and the perspective of copyright law.

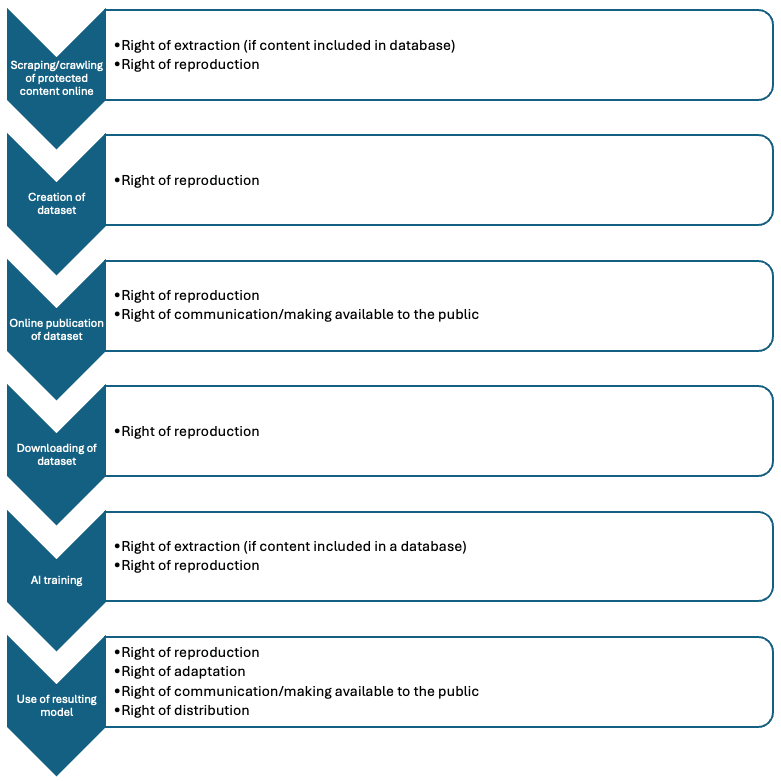

The diagram below offers a simplified guide of the stages of AI model development that could involve copyright-relevant acts:

Some eminent commentators nevertheless submit that existing exceptions like the EU TDM ones could cover unlicensed AI development fully, provided that the three-step test is not construed as a “backdoor for declaring the TDM provisions inapplicable in GenAI training scenarios” (M Senftleben, ‘Are the European TDM Exceptions Applicable to GenAI Training? Despite the Three-Step Test?’ (Kluwer Copyright Blog), 1 October 2025).

Like all exceptions, the TDM ones also need to comply with the three-step test and, having regard to the UK, fair dealing. Hence, Article 7(2) of the DSM Directive does not introduce an “additional rule” or requirement. It reinstates a basic fact, which stems from international law: exceptions must be limited to certain special cases, which do not conflict with the normal exploitation of protected content and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of rightholders.

The three-step test consists of three cumulative requirements, which need to be assessed in accordance with their logical order, that is as steps. Before determining whether a certain exception unreasonably prejudices the legitimate interests of the concerned rightholder, it is necessary to consider whether there is a conflict with a normal exploitation of protected content and, prior to that, whether the exception at hand only applies to certain special cases (WTO, United States – Section 110(5), §6.160; see also Guide to Copyright and Related Rights Treaties Administered by WIPO and Glossary of Copyright and Related Rights Terms, para 85).

AI training in light of the three-step test / fair dealing requirements

Applying all of the above to AI training, not only is there no TDM exception (or open-ended fair use doctrine) covering in every instance the entirety of it, but such an exception also would not be possible considering the requirements of the three-step test / fair dealing. To be clear: not all AI case studies can be treated alike, including from a copyright perspective. For example, an AI tool that helps physicians with their diagnostic assessments is different from an AI service that produces songs that compete with, if not replace, human-generated songs.

A different interpretation would (i) arguably render an exception applicable well beyond “certain special cases” – thus disqualifying it at the outset given that, as noted, the steps of the three-step test must be considered in sequence – and (ii) seem to be clearly at odds with the second and third step.

No conflict with normal exploitation

The concept of ‘normal exploitation’ includes both existing licensing practices and emerging or potential markets. This was clearly spelled out in the WTO panel decision in United States – Section 110(5). When an exception has the potential to reduce the volume of sales or of other lawful transactions relating to protected works (ACI Adam, para 39) up to the point that exempted uses enter into economic competition – even potentially – with non-exempted ones, then such a provision is incompatible with the second step of the three-step test (United States – Section 110(5), §6.181).

This also aligns with UK fair dealing and fair use doctrines, including the US one.

Under UK law, the most important fairness factor is the degree to which the alleged infringing use competes with the exploitation of the copyright work by its owner. Such a competition should be intended as extending to any form of activity which potentially affects the value of the copyright work.

In Goldsmith the US Supreme Court recalled, by reference to Campbell, that the central question under the first fair use factor (‘purpose and character of the use’) is whether the use supersedes the plaintiff’s work or rather adds something new, with a further purpose and character that goes beyond what is required to qualify as a derivative work. If the original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purpose and the latter is commercial, this is likely to weigh against a finding of fair use. As to the fourth fair use factor (‘effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work’), this requires considering not only the actual market/value of one’s work, but also the potential market/value.

The guidance above was convincingly applied in the first US case on unlicensed AI training, Thomson Reuters, in which Circuit Judge Bibas found that the defendant’s unauthorized use of the plaintiff’s content was an infringement.

Along similar lines, in Kadrey, Judge Chhabria noted that “in most cases” the unlicensed use of protected content for training purposes would be regarded as illegal, if resulting AI models are expected to generate billions, even trillions, of dollars for their developers. It would be “ridiculous” to claim that such companies cannot “figure out a way to compensate copyright holders” for the use of their content, if this is required for training purposes. The judge also criticized the earlier order issued by Judge Alsup in Bartz, especially that he had appeared to overlook the substantial displacement effects of AI-generated content flooding the market and the reduction of incentives to create in the future.

In light of the above, one is left wondering how – as suggested by some commentators – AI developers seeking licences from rightholders would be harmful to rightholders. Considering in particular that a licensing market – both individual and collective licences – for training purposes is already here and rapidly developing (see further below).

No unreasonable prejudice

It is a settled principle of copyright law that the exclusive rights granted under it are proprietary (in line with Article 17(2) of the EU Charter) and preventive in nature. In line with the provisions of the Berne Convention, protection includes both the enjoyment and exercise of such rights. In turn, the third prong of the three-step test analysis does not mean that one only needs to consider economic harm, so that receiving remuneration without the possibility of control would be a "win-win".

Also aligned with consistent CJEU case law, copyright's exclusive rights are – as recalled – preventive in nature and exceptions are, indeed, an exception to this rule. Moreover, it is questionable whether mere remunerative rights would provide rightholders strong enough negotiating position to enable them to obtain appropriate remuneration for the use of their rights. If not, downgrading exclusive rights to remunerative rights would appear to lead to “unreasonable prejudice”, also when pure economic harm is considered.

As explained by Arnold J (as he then was) in Tixdaq, the final step of the three-step test “requires consideration of proportionality, and a balance to be struck between the copyright owners' legitimate interests and the countervailing interests served by the exception”.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, a handful of jurisdictions around the world have adopted limited exceptions allowing, under certain conditions, TDM. At this stage, the borders of such provisions remain mostly untested and further litigation will continue to emerge – at least in the short- and medium-term.

That said, a licensing market for AI training is quickly developing. As reported in the media, agreements have been already concluded between rightholders and AI developers, in particular in news media (such as Axel Springer’s, Financial Times’, Hearst’s, and Reuters’ partnerships with Open AI and Microsoft, and Prisa Media’s partnership with OpenAI and Perplexity) and music sectors (including Stable AI’s launch of its licensed Stable Audio 2.0 model, or ElevenLab’s launch of Eleven Music in partnership with Merlin and Kobalt), and more appear to be on their way.

All of the above indicates that – going forward – the applicability of exceptions will be likely confined, as a matter of practice, to ‘certain special cases’ and very circumscribed phases of AI development. Licensing, not exceptions, appears therefore to be the most practical and – above all – practicable framework for accommodating AI development and striking the required ‘fair balance’ with copyright protection.

[Originally published on The IPKat on 13 October 2025]